By Başak Balkan

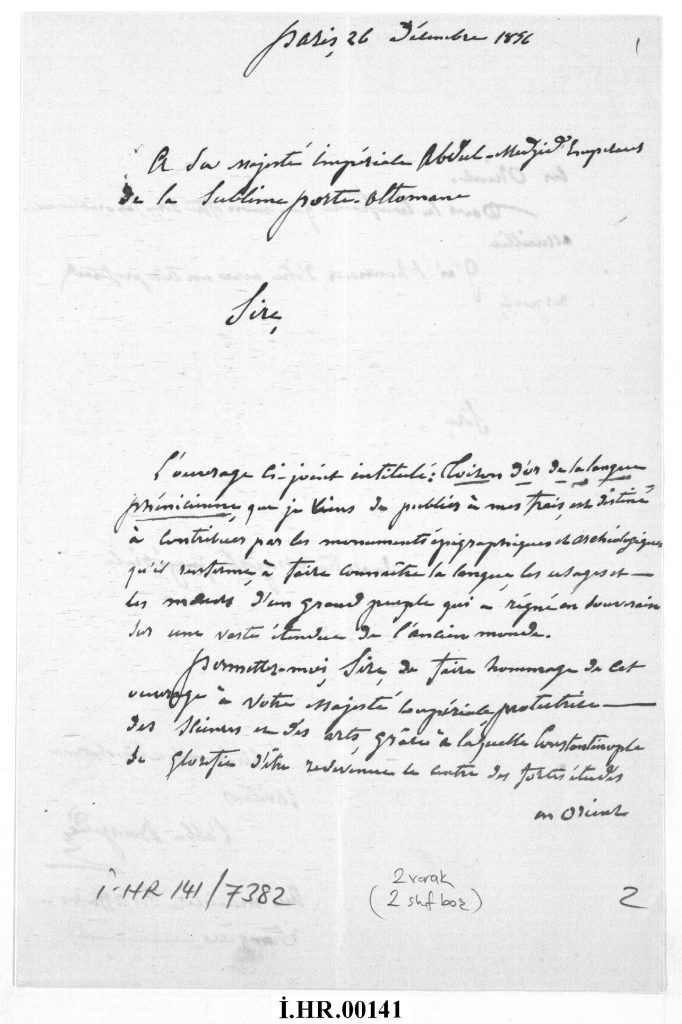

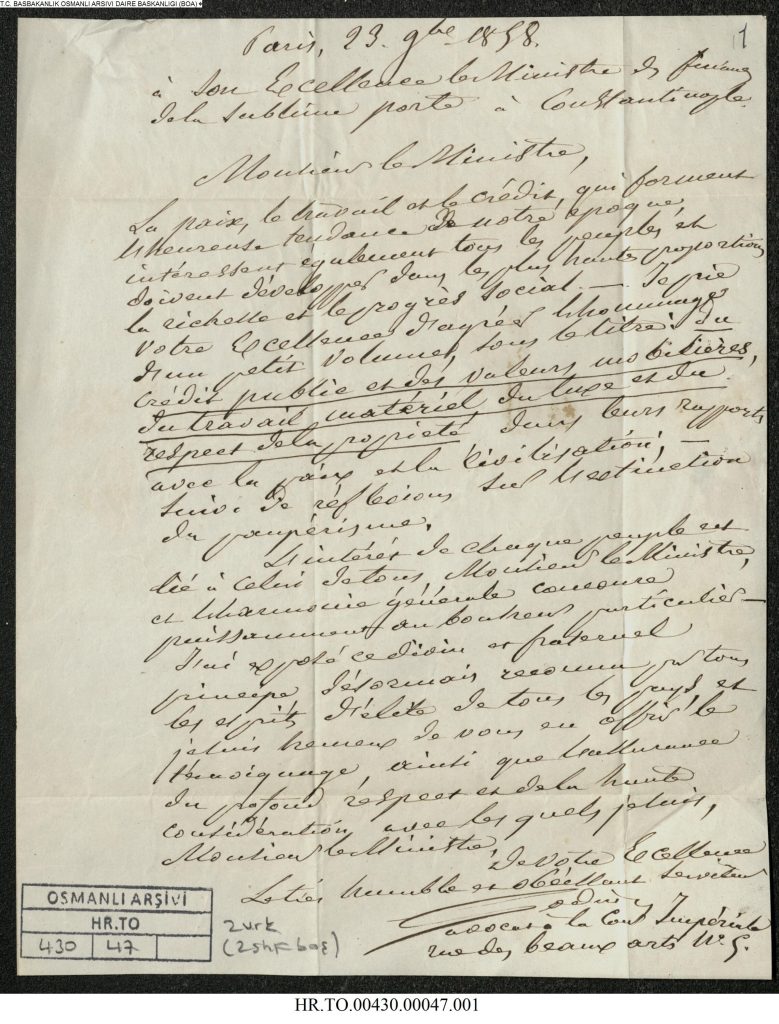

In 2019, I translated five academic articles from Turkish into English, on how and what people read in the Ottoman Empire.[1] It was one of the most rewarding assignments I have ever had. My reviewer was a young American academic living and working in Istanbul. We became pen-pals, then finally met a few years later. It’s thanks to him that I was able to work on a Turkish Assistant Professor of History’s exciting research project, Books for the Sultan: European Authors and Book Diplomacy in the Ottoman Court in the Mid-19th Century. She sent me a first batch of scanned, handwritten letters in French from the mid-19th century in June 2022. I would end up translating several batches letters into English, by August 2023. Nearly all were penned by francophone authors seeking, amongst other things, permission to dedicate their books to the Sultan.

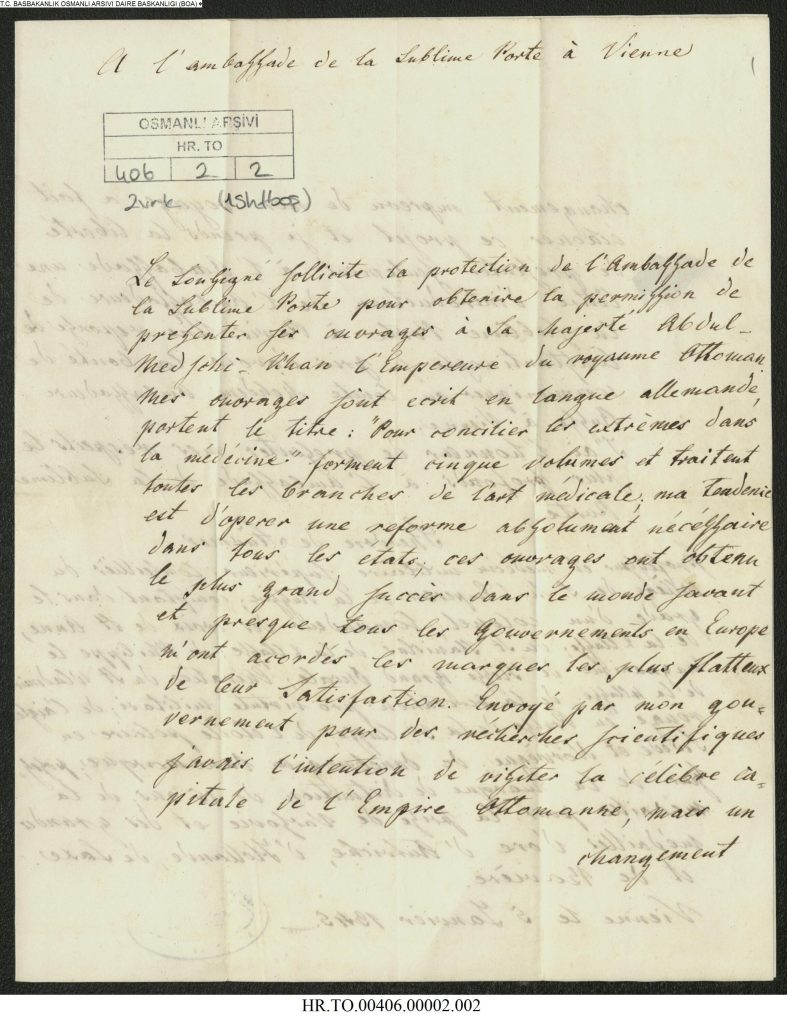

I opened the first one. What had I got myself into? The first letter, by

Théodore de Stürmer, professor and superior military doctor, adviser to the college of His Majesty the Emperor of Russia, rank of colonel, commander of the crosses of Sainte-Anne of the 2nd class, of Saint Stanislas of the 2nd class, of the Order of Merit of Philip the Magnanimous of the Grand Duchy of Hesse, knight of Saint Vladimir of the 4th class of the decoration Pro Virtute Militari, of the Red Eagle in Prussia of the 3rd class, of the Polar Star in Sweden and Norway, the Danish Order of the Dannebrog, recipient of the mark of distinction of fifteen years, of the Medal For the Taking of Warsaw, and of the great gold medals of Austria, Holland, Saxony and Bavaria[2]

was nearly illegible. And after that, every letter presented a different challenge. Some were written in the kind of cursive that would make a modern calligrapher weep with envy – and, at times, frustration. I found myself zooming in, then zooming even closer (fortunately, the scans were of superior quality) and summoning every ounce of patience to make out scribbles worse than a doctor’s script. When defeated, I turned to Google, trying variations of a name or place or the name of a medal, placing the approximate spelling of an author’s name along with his book’s deciphered title. This detective work was both thrilling and time-consuming, not only because some cases were tough to solve, but mostly because I invariably got caught up in the author’s life story. How had these people managed to squeeze so much into a single life? They were well-travelled, they had participated in revolutions, in wars, they had written books, been married, had children, they were suddenly to be found serving the Ottoman Empire in an official position and then again writing books that sometimes had nothing to do with their occupations. So many polymaths, looking for fame, money, knowledge, adventure or stability. When I found online a book for which an author had solicited funds, or had mentioned wanting to dedicate to the Sultan, I felt a warm rush of connection. I thought, ‘So you really did write it. His Highness really did condescend to accept the dedication of your work!’ It was as if I had spent time with a time traveller who had told me about his aspirations, then had gone back to his own time, leaving me to look for traces of what had happened to him afterwards. I was even more proud of my author when I saw that his books were still in print, nearly two centuries later.

I immediately realised that translating directly from the manuscripts was impossible. My puny brain couldn’t simultaneously decipher the handwriting and translate. I adopted a three-step approach: first, I dictated/transcribed the entire file into French, putting in XXX when I couldn’t read a word. Second, I lost myself in rabbit-holes as I conducted research trying to fill in the XXXs. Then I steeled myself for the translation process.

The formatting of these letters was peculiar, by 21st century standards (wait – we no longer have standards for handwritten letters, because we don’t write any!). Most authors left a wide margin on the left side, and some crammed all the letters towards the right side of the page, sometimes even continuing downwards, instead of hyphenating. When they did hyphenate, they didn’t do so by syllables, just randomly. ‘f’ was often used instead of ‘s’, and words like Ambassade would appear as ‘Ambafsade’ or ‘Ambaffade’. To avoid starting a new word at the end of a line, some writers drew a long (sometimes decorative) line to fill the space. They all ended with the same formula: “J’ai l’honneur d’être avec un profond respect, Monseigneur, de votre altesse, le très humble et très obéissant serviteur”.

Some letters appeared hastily written – I could almost hear the pen scratching across the delicate paper. Others seemed to have been carefully crafted for hours. For emphasis, some writers would boldly retrace certain words, use larger lettering, or underline phrases, occasionally several times. The dates, addresses and signatures were typically found at the end of the letters. The recipient’s name and title were written at the top, like an ornate header.

The contents of the books mentioned in the letters were incredibly diverse: treatises on gemstones, manuals on horseback riding, guides to sword fighting, detailed histories of Montenegro, Abyssinia, China and Cyprus; “electricity in medicine”, wastewater management, vaccination, how to improve the Empire’s finances, a request for information on every facet of the Empire which served to produce an extremely detailed book which remains an important reference still today.

The flattery and the bureaucracy were wonderfully fun to translate. Some made me think of the series Yes Minister:

Monseigneur,

J’ai eu l’honneur de recevoir la dépêche que Votre Altesse a bien voulu m’adresser en date du 7 de ce mois pour me transmettre les ordres de Sa Majesté Impériale notre auguste souverain d’exprimer à monsieur le ministre des Affaires étrangères de Sa Majesté Sarde la haute satisfaction de Sa Majesté pour l’offre que le gouvernement royal de Sardaigne a fait au gouvernement impérial de deux exemplaires de la statistique criminelle des États Sardes pendant l’année 1853.

Je me suis empressé de m’acquitter des ordres que me transmettait Votre Altesse et d’exprimer à Monsieur de Cavour, tant par écrit que de vive voix, les sentiments de Sa Majesté Impériale à cette occasion.

J’ai l’honneur d’être avec un profond respect, Monseigneur, de votre altesse, le très humble et très obéissant serviteur,

Rustem[3]

Or:

Majesty, to whom belong excellence and magnificence, Majesty whom everywhere one hails for his good deeds, exalts for his merits, Protective Majesty, honoured and blessed, Civilising and regenerating Monarch,

May I lay at your feet a poem in your honour, in your praise, recently published by me in French verse, and translated into Turkish prose by a high official of your Sublime Porte?

[…two pages more of sycophancy…]

God grant, Majesty, that radiant days descend upon your head in as great numbers as He sows golden stars in your most beautiful summer nights! May God allow streams of joy to flow over your heart, no less innumerable than the ripe dates he causes to fall from a forest of palm trees! May the Most High eternalise your reign for the happiness and glory of the East, for the sweet peace of the West! May your name and your memory live in the pages of historians and on the sheets of poets as long as literate fingers marry syllables and the bird sings on the branches!

I withdraw, Majesty. I leave it to those of your ministers who put the lips of Europe on the lips of Turkey, I leave it to the great writer, to the great statesman who reads as deeply into the dawn of the future as into the evening of the past, the benevolent task of presenting directly my humble and sympathetic offering to Your Majesty. I am but a stream, carried by the river to the sea.

I respectfully kiss from afar, Majesty — too far, to my great regret, your loyal hands which have always extended friendship towards France. I kiss those august hands which, as I stated in my Ode, hold the torch of progress with the same vigour as the sword of combat. I kiss those powerful and generous hands which know so skilfully how to direct the reins of a great empire and distribute to all justice, good grace and munificence.[4]

It was pure joy to translate that one!

As you can see, the letters didn’t ask only for permission to dedicate a book to the Sultan or his ministers. Some authors only wanted to present a book to the Sultan so it could take its place on the Royal Shelves. There were those who asked for financial support to continue research or undertake travels for scholarly purposes. A few asked for an official position. One or two were hell-bent on collecting medals. Some others seemed to sincerely want to aid the Empire in improving its finances or water system, or to help it to have a better image in Europe, to propagate news of the reforms undertaken by Sultan Abdulmejid, to fight against misinformation being spread by foreign forces (the owner of the French-language newspaper in Smyrna, Anthony Edwards wrote, in one of the most interesting letters of all, “I believe I have done some good, straightened out some erroneous opinions. And the time has come for Turkey to act also through the press, to work on public opinion, to unmask, by this powerful means, the plots that are being woven against her, to communicate to all propagandists that a vigilant eye is closely monitoring their machinations.”[5])

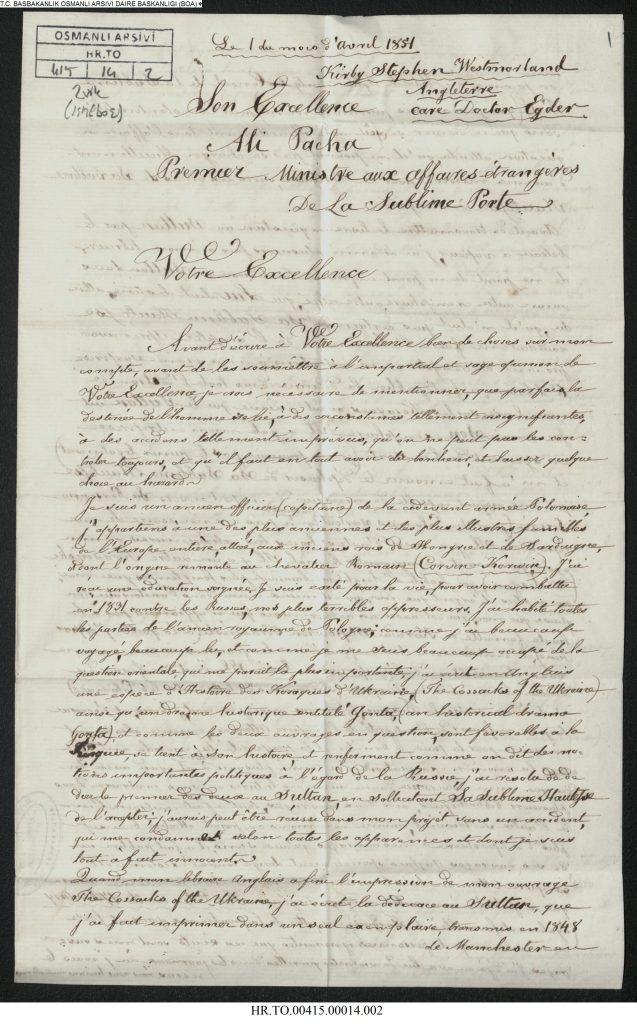

One of the letters I most enjoyed reading was that written by a former captain in the Polish army, and now an exiled writer in England, Henryk Count Krasiński, whose whole letter consisted of a single, loud wail of complaint. He came from one of most illustrious families in all of Europe and was now in exile for having fought against the Russians in 1831. His greatest wish was to dedicate his book, The Cossacks of the Ukraine to the Sultan:

Avant de transmettre le livre en question au Sultan par le bateau à vapeur, j’ai ordonné plusieurs fois à mon libraire de ne point imprimer la dédicace au Sultan dans aucun autre exemplaire, outre celui qui lui était destiné, attendu qu’il n’était pas certain que Sa Sublime Hautesse voudrait me faire l’honneur de l’accepter. Après avoir promis de respecter mes instructions, à ma grande surprise, ce libraire a fait publier la dédicace dans toutes les éditions de mon livre sur les Cosaques, avant même que le Sultan eût pu recevoir Son exemplaire. Il a gâté mon entreprise en agissant de la sorte (je ne pouvais pas le punir légalement) et m’a fait encourir le déplaisir que Sa Sublime Hautesse qui, me croyant capable de manquer de respect envers Sa Personne Sacrée (pour un Polonais surtout, un crime ?), n’a pas cru nécessaire de me répondre. Il y a aussi d’autres choses très extraordinaires à mon égard qui est eussent pu augmenter le mal. Il y a un autre Krasinski (Waleryan) qui habite l’Angleterre, beaucoup plus longtemps que moi, qui a plus d’argent que moi, qui est mieux connu dans l’aristocratie anglaise que moi, qui est aussi un auteur, mais qui n’appartient pas à la haute famille de Korwin Slepowron Krasinski (à laquelle j’appartiens) et dont le nom était imprimé dans les journaux russes comme sous-chambellan de l’empereur de Russie. Il écrit en faveur du démembrement de la Turquie (son cousin s’est battu contre les Polonais). C’est à dire contre la Turquie, tandis que moi, j’ai écrit, j’écris et j’écrirai toujours en faveur de l’intégrité de l’empire Ottoman, comme absolument nécessaire pour la paix, le bien-être et la prospérité du monde entier, sans la moindre exagération, j’ai donné plusieurs lectures à cet égard aussi, tandis que mon adversaire donne aussi des lectures pour dire le contraire. Dans plusieurs bibliothèques, nos deux ouvrages, tout à fait contraires l’un à l’autre, se trouvent l’un à côté de l’autre. Néanmoins, on parait attacher beaucoup plus d’importance à mes ouvrages qu’aux siens, il a fait publier un de ses ouvrages en anglais spécialement dirigé contre l’existence de l’empire Ottoman dans le même endroit et chez le même libraire qui a publié mon autre ouvrage anglais: The Poles in the 17th century (également favorable à la Turquie) pour jeter de la poudre aux yeux et faire croire à beaucoup de personnes ignorantes que ces écrits sont mes ouvrages. J’ai déjà eu avec lui de violentes querelles dans les journaux où j’avais le dessus. Nous nous haïssons mutuellement.[6]

He ends his letter proposing to launch a pro-Turkish journal distributed free to British MPs as a “counterweight to Russian attacks.” Boasting friendship with famed generals, he audaciously asks to become an Ottoman consul in England, offering to buy weapons for the Ottoman Empire. With hints of grandiose delusions, Krasinski pledges fervent loyalty if granted the Sultan’s “confidence.”

When I did some research into this poor Henryk Krasiński, I found a bit of gossip about him in a letter from one Polish émigré to another – it’s hilarious:

Henryk Krasiński is not alone in his misfortune; he is equally unhappy everywhere. Whether he strikes the chord of love, he encounters only thorns and obstacles; whether he strikes the chord of literature, he faces only disappointments and even prejudices. Nowhere does he find understanding. Krasiński sees those less worthy as happy; he never finds himself among them. What a conspiracy of fate! […] However, he attributes his failure to spells. There is another Krasiński here, Walerian Krasiński. Henryk Krasiński has great suspicion that Walerian Krasiński, wherever he can, spoils his affairs, using the same surname and the same title, with a slight difference in their first names. Hence the source of his misfortune.[…][7]

See what research vortexes I kept getting lost in?

There is also the heart-wrenching case of three Italians who had been languishing in a Turkish prison. They had no book to promote, they simply had

l’honneur d’exposer à Son Altesse, que condamnés pour sept ans, nous gémissons dans les prisons de l’Arsenal. Nous avons souffert en silence, sans bruit et sans scandale.

Dans ce moment, nous nous trouvons au fond de la prison, éclairés seulement d’une petite lampe, trainant une longue chaîne, couchés sur la terre humide, passant les nuits entières sans dormir et n’ayant chaque jour que deux petits pains et de l’eau.

La grâce que demandent les soussignés à Son Altesse, est celle de vouloir bien nous mettre au nombre des pardonnés par Sa Majesté le Sultan Abdul Medjid. Il ne manque que deux mois pour terminer les sept années de notre condamnation.

Nos femmes et nos enfants plongés dans la plus profonde misère depuis notre emprisonnement se joignent à nous pour implorer la grâce de notre liberté. Ils nous aideront aussi à vous témoigner notre profonde reconnaissance en demandant à Dieu, qu’il daigne répandre sur vous ses bénédictions les plus abondantes et vous accorder la récompense qu’il réserve aux cœurs compatissants.

Nous avons l’honneur d’être, de Son Altesse, les très humbles serviteurs,

Giuseppe Franconli,

Gavrili Luca,

Giorgio Tirnovgli [?][8]

Although I looked up all three names, I couldn’t find anything about these unfortunate men. I suppose this letter got mixed up with the others by mistake, and although it made my heart ache, I was glad to have a thought for them. Why did they wait six years and ten months to write this plea?

—

Going back to all these letters to write this article, my head is filled with hundreds of voices, murmuring, wailing, coaxing, boastful, hopeful voices, speaking with all types of different accents. This Assistant Professor brought them back to life, to demonstrate that intellectuals also make history (but not in circumstances of their own choosing) just as much as statesmen, not through wars and treaties, but through interpersonal relations and the sharing of books and knowledge. And we, the translators, play a big role in this – after all, who was translating all those letters for the Sultan? The significance of our role has always extended beyond mere translation; it involves bridging cultures and fostering mutual understanding. In every carefully translated word, we carry the weight of history, the nuances of context, and the essence of the original message.

And here’s a final tidbit of information – between 1852 and 1882, three of the Sultan’s Grand Viziers embarked on their careers as dragomans[9], highlighting the importance of linguistic and diplomatic skills in Ottoman governance and foreign relations. This compels me to cry out: Translators and interpreters of the 21st century! Rise to the challenge of shaping diplomacy and politics! Look at what our forefathers were capable of!

With that, I have the honor to be, with deep respect, Dear Reader, your most humble and obedient servant.

Başak Balkan is a Turkish translator and interpreter. She works between Turkish, English and French and, when not travelling, lives in Belgium.

[1] https://sharpweb.org/linguafranca/issue-5-2019-ottoman-print-culture/

[2] To the Embassy of the Sublime Porte in Vienna, dated 5 January 1845.

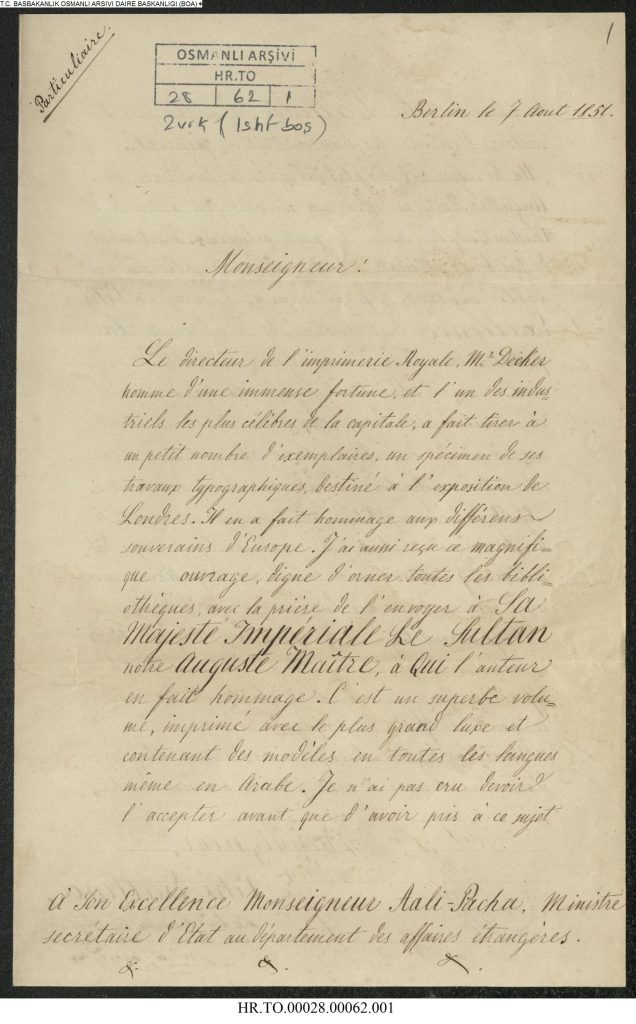

[3] Rüstem Bey, the Ottoman diplomatic agent in Turin, to Ali Pasha, the minister of Ottoman foreign affairs, dated 22 October 1857.

[4] Edouard Gouin, Member of the Historical Institute of France, Ex-chargé de mission of the Emperor, to Le Padischah Abd-ul Aziz Khan, dated 20 September 1866.

[5] To His Excellency Ali Effendi, Minister of Foreign Affairs, dated 7 January 1848

[6] Idem, dated 1 April 1851

[7] Letter from Leonard Niedźwiecki to Eustachy Januszkiewicz dated 27 June 27 1839. http://www.historycy.org/historia/index.php/t118137.html

[8] Undated, addressed only to “Altesse”

[9] Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha: Served as Grand Vizier multiple times between 1852 and 1871.

Began his career as a dragoman in the Ottoman Embassy in Vienna and later in London.

Keçecizade Mehmed Fuat Pasha: Held the position of Grand Vizier twice, from 1861 to 1866 and briefly in 1869.

Started his diplomatic career as a dragoman and later became a prominent statesman and diplomat.

Ahmed Vefik Pasha: Served as Grand Vizier briefly in 1878 and again in 1882.

Initially worked as a dragoman and interpreter.